Tags

Abigail Klein Leichman, Accident Analysis and Prevention, athlete, automobile, background music, bass guitar, Ben-Gurion University of the Negev, biology, Cadillac, car, CD, Chevrolet, compact disc, Eminem, emotions, General Motors, Hahnemann Medical University, hand-clapping, in-car entertainment, Israel Defense Forces, Israel National Road Safety Authority, Israel21c, Jerusalem, John Sloboda, Keele University, Levinsky College, medical school, mental health, Micha Kizner, music cognition, music therapy, Nachal Troupe, percussion, Philadelphia, phobia, psychology, Rubin Academy of Music and Dance, Saturday Night Live, soldier, stage fright, Tel Aviv, Tina Fey, traffic safety, Transportation Research, Warren Brodsky, Zack Slor

Listening to music in the car affects the way you drive, but whether it’s Bach or Eminem doesn’t matter. The trick is to choose tunes that do not trigger distracting thoughts, memories, emotions or bopping along to the beat. This takeaway message from an Israeli study was all over the Internet, US news programs and international newspapers months before it appeared in the October 2013 edition of Accident Analysis and Prevention.

Listening to music in the car affects the way you drive, but whether it’s Bach or Eminem doesn’t matter. The trick is to choose tunes that do not trigger distracting thoughts, memories, emotions or bopping along to the beat. This takeaway message from an Israeli study was all over the Internet, US news programs and international newspapers months before it appeared in the October 2013 edition of Accident Analysis and Prevention.

The media attention has put lead researcher Warren Brodsky, director of music science research at Ben-Gurion University (BGU) of the Negev, in the limelight more than any of his previous findings in music cognition and has illuminated his research path for possibly the rest of his working days. “It seems that every aspect of my career has led me down this path,” Brodsky says. The study also was notable in scientific circles because it was commissioned by the Israel National Road Safety Authority, making Israel the only country in the world to fund an investigation of how background music puts drivers at risk for distraction.

Brodsky had long been interested in this phenomenon, given that people in modern cultures listen to music more in their cars than anywhere else. “I wondered how listening to music affects driving behavior and how the car environment influences what kind of music we listen to,” he says.

In 2002, Brodsky published the first study to show that fast-paced music directly causes accelerated driving speed. “It was perhaps a small study, but it made a huge splash around the world,” he says. Indeed, his finding even merited a mention on Saturday Night Live. Comedian Tina Fey reported: “A new study shows that drivers who listen to fast tempo music while driving have more accidents, while drivers listening to slow music have sexier accidents.”

Born in Philadelphia, Brodsky moved with this family to Jerusalem at age fifteen. After high school at the Rubin Academy of Music and Dance, he played bass guitar with the well-known army band, the Nachal Troupe, and then returned to Rubin in 1982 to earn a bachelor’s degree in percussion and music education.

His performances for soldiers had left him intrigued as to how music affects well-being. Music therapy was not yet taught in Israel. He later became one of its pioneers by earning a master of creative arts in music therapy at Hahnemann Medical University in Philadelphia, the only graduate program of music therapy within a mental health department of a medical school.

Returning to Israel, he worked in special-ed schools, state hospitals and mental health clinics. He began training music and movement therapists at Levinsky College in Tel Aviv in 1986 and was among the first to get licensed by Israel as a creative and expressive arts therapist.

In 1992, Brodsky and his family went to England for three years so he could study toward a doctorate in music psychology at Keele University under the mentorship of the renowned John Sloboda. “I was interested in new fields like the biology of music-making, music medicine and performing-arts psychology,” he says.

His work in the UK influenced British medical associations to rethink “stage fright” as an occupational hazard, rather than a mental health weakness or social phobia, that might best treated by clinicians with a background in music. “It was important for the field that a new breed of musician, with clinical training and psychotherapeutic experience, take responsibility of how to treat performing musicians in the symphony orchestra, just as athletes might get counseling from a sports psychologist,” he says.

The research bug had bitten Brodsky, and the effects were permanent. “I couldn’t go back to the therapeutic arena after that. My heart wasn’t in the clinic, and my passion to treat patients had been replaced by a deep passion and infatuation for empirical work.” He won a post-doc fellowship at BGU in the behavioral sciences department and later became tenured as senior lecturer of music. Brodsky is the sole teacher of music courses in the Faculty of Humanities and Social Sciences.

In 2008, Brodsky did a proof-of-concept study commissioned by General Motors about how music might strengthen brand identity of Chevrolet and Cadillac automobiles. He has also published investigations on hand-clapping songs of elementary school children and positive aging among orchestra players. Then, in 2010, the Israel National Road Safety Authority provided funding to Brodsky for a large-scale on-the-road study involving young drivers. “It seemed like this was my calling. No one else in the world was invested in researching the effects of music on driver behavior – not from the field of music psychology or traffic safety,” he says.

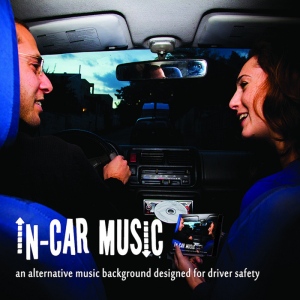

Previously, Brodsky and Israeli music composer Micha Kizner, a former buddy from the Israel Defense Forces (IDF) Entertainment Unit, devised a program of original music carefully structured to increase driver safety and published pilot studies in the journal Transportation Research. With this CD in hand, Brodsky and co-researcher Zack Slor recruited eighty-five young drivers to drive several forty-minute trips with either their preferred cruising tracks brought from home or with the experimental CD. The results show a clear twenty percent decrease in driver errors, miscalculations and aggressive driving accompanied by the alternative background music.

“Bottom line, the car is the only place in the world you can die just because you’re listening to the wrong kind of music,” says Brodsky, who is writing a book on the topic.

“Maybe we have to educate the public at large. There is a need to raise awareness and to teach drivers new practices of everyday music consumption and how to make better choices for roadway listening. It’s a question of being more careful about preferences and exposure. In the end, it is an issue of health and well-being, not in-car entertainment.”

Abigail Klein Leichman – Israel21c