Tags

architecture, ballet, Bavarian State Ballet, cello, choreography, dance, death, globalization, LG Arts Cente, Mikhaylovsky Theatre Ballet, Multiplicity Forms of Silence and Emptiness, Munich, National Spanish Dance Company, Norwegian National Ballet, organ, Seoul, Universal Ballet

Playing a cello in human form

Europe during the Baroque era, a period and artistic style that prevailed in the seventeenth century, was dominated by a series of great musicians who are beloved to this day. Among them is Johann Sebastian Bach (1685-1750), the great German musician and composer. Dubbed the “Father of Classical Music,” Bach has been much-loved worldwide for more than three centuries.

Many countries around the world have seen both dead and living musicians and artists inspired by the legendary composer’s music. In Korea, too, there is no doubt that the artistic and musical scenes have been much-influenced by his music over the recent globalized decades.

A new piece on the stages of Seoul has now proved that Bach is ever-renewable, this time in the form of a ballet. Multiplicity, Forms of Silence and Emptiness is a ballet featuring the well-known Baroque compositions of Bach. It ran for three days, from 25 to 27 April 2014, at the LG Arts Center in central Seoul. As one can see from the title, the piece aims to deliver the “multiplicity” of artistic elements that exist in Bach’s music, as well as in other forms of art, architecture and dance from the Baroque period during which the composer lived. The choreography also illuminates some important moments of Bach’s life, emphasizing his passion for his music and showing the loneliness and sometimes painful illnesses that were part of his inspiration.

The piece is being presented by Universal Ballet, one of Korea’s major ballet companies. Universal Ballet is now the fifth troupe to perform the work, following the National Spanish Dance Company, the Norwegian National Ballet, the Bavarian State Ballet in Munich and Russia’s Mikhaylovsky Theatre Ballet. “As a long-time fan of this work, I am so happy to be able to bring such great art to Korea,” said general director Moon Hoon-sook of Universal Ballet. This work, she added, has always been both one which she wanted to present as a dancer and one which she always wanted to view from the audience.

The ballet features twenty-three Bach compositions, arranged into two acts. Act One is centered on the signature arts of the Baroque period and on the life of the composer himself. It featured a series of choreographed dance moves, all inspired by Bach’s music, as the dancers wear simple black costumes and dance as if they are each a musical note in Bach’s composition, acting like musical instruments and performing the sounds they make. In one of the more memorable scenes, a male dancer, portraying Bach himself, plays a human cello formed by the arch of his counterpart’s body. The choreography shows the audience the way in which Bach, through his music, became one with his musical instruments.

Act Two focuses on Bach’s final years with their string of hardships, agonies and, finally, in the end, death. The emptiness and loneliness the musician felt in his later years is exquisitely displayed by a group of seven male performers dancing to solemn organ music. Meanwhile, a female dancer, wearing a white mask, symbolizes Bach’s purity and also the conflict he felt between his music and religion, a conflict from which he suffered until his death. In the final scene, Bach is at death’s door and collapses onto the floor as black-clad dancers stand behind him, like a series of musical notes, dancing to the rhythm. The scene gives the audience an important message: even though he dies, the musical legacy he left behind is everlasting.

Choreography for the show comes from Spanish artist Nacho Duato. “At first, I was so afraid of the idea of having to choreograph a piece based on Bach’s music,” Duato said at a press conference on 21 April 2014. “His music is so great and beautiful that I thought, ‘How dare do I have my humble, dirty hands do something with his music?’ I felt so scared at first,” he confessed. “As a choreographer, I wanted to show my sincere respect for the great musician through this work. I had to be careful, out of my deep respect for his music, in choosing some of Bach’s pieces that I thought would be most suitable for dancing.”

Sohn JiAe – The Inside Korea

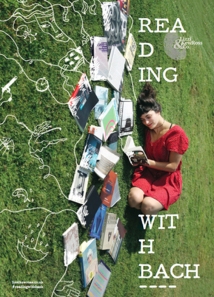

Lizzi Kew Ross and Co.’s Reading with Bach brings us dancers and musicians into the territory of books. Reading with Bach is a kind of excavation, where the real and imagined worlds collide. Through movement and music, we watch, see, listen, engage and speculate on that strange, solitary act that is reading.

Lizzi Kew Ross and Co.’s Reading with Bach brings us dancers and musicians into the territory of books. Reading with Bach is a kind of excavation, where the real and imagined worlds collide. Through movement and music, we watch, see, listen, engage and speculate on that strange, solitary act that is reading. Underpinning so much of Sir John Eliot Gardiner’s approach to Bach is identifying the provenance and essence of dramatic character, “mutant opera” (as Gardiner calls it) found in genres – like the

Underpinning so much of Sir John Eliot Gardiner’s approach to Bach is identifying the provenance and essence of dramatic character, “mutant opera” (as Gardiner calls it) found in genres – like the