Tags

accordion, apartheid, aria, Arthur Astier, blues, Can Themba, Center for Performance, dance, Death and the Maiden, Franck Krawczyk, Freud Playhouse, gesture, guitar, Ivanno Jeremiah, Johannesburg, Jordan Barbour, Los Angeles, Marie-Hèléne Estienne, Mark Christine, Mark Kavuma, Mark Swed, Mozart, Newton, Nonhlanhla Kheswa, opera, Othello, Peter Brook, piano, Schubert, Shakespeare, Sophiatown, St. Matthew Passion, Thèâtre des Bouffes du Nord, The Blue Danube, The Los Angeles Times, The Magic Flute, The Suit, theatre, trumpet, University of California

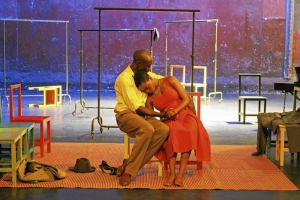

Ivanno Jeremiah and Nonhlanhla Kheswa

The earth did quake; the rocks rent, and the graves were opened. Then peace was made with God as Jesus’s body came to rest. That peace, and with it the ability to notice beauty in all things, is expressed in the last aria of Bach’s St. Matthew Passion (BWV 244b) which begins with the text, “Make thyself clean, my heart.”

This aria is among the most sublime gifts given in all of music, a vision far better suited for the soul than the stage. Yet Peter Brook tailors it meticulously to The Suit. The 89-year-old British director’s production of a short play based on a story by South African novelist Can Themba ends with this astonishing aria plucked out on dinky electric keyboard rather than sung as though musical lava profoundly pouring from a deep bass. Brook has no pretense to present Bach as a call to hope on a cosmic, landscape-altering scale. It is enough that we carefully sustain beauty in the atmosphere of tragedy.

The latest production from Brook’s French company, Thèâtre des Bouffes du Nord, has arrived in Los Angeles. Under the auspices of Center for Performance at UCLA, The Suit is currently finishing up a two-year international tour and will run through 19 April 2014 at Freud Playhouse. A simple show, it employs only three actors, three musicians and a few basic stage properties, such as chairs and clothes racks.

Philemon (Ivanno Jeremiah) discovers his wife, Matilda (Nonhlanhla Kheswa), in bed with another man. The lover flees, leaving his suit behind. The earth does not quake. There is no violence, no lack of civility. Philemon merely insists that the suit be treated as a guest of the house, a diplomatic reminder of his wife’s offense. Otherwise life goes on.

But life going on is no small thing. The setting for The Suit is the township of Sophiatown west of Johannesburg during apartheid. It wasn’t pretty and pink, Philemon’s friend, Maphikela (Jordan Barbour), tells us. But it was alive.

People lived ordinary lives, indulged in pleasures and tried not to think too hard about the oppression lurking around the corner, about the white police who took pleasure in cutting off the fingers, one by one, of a black guitarist before shooting him. They tried not to think about the fact that Sophiatown would soon be leveled and its residents relocated to a camp.

Brook lets the story tell itself. These are gracious characters, enormously appealing. But humiliation is discretely poisoning the atmosphere.

The play has the quality of a twentieth-century South African Othello. In Shakespeare, jealously is like an unsubtle Newtonian force, namely explosive. A Moor stands apart and is unable to control his emotions. There is clear-cut black and white. Iago, who taunts Othello, is all bad. In Sophiatown, white suppresses black. But Themba’s story – as adapted by Brook, Marie-Hèléne Estienne and composer Franck Krawczyk – is of blacks. Maphikela is not Iago. He reluctantly tells Philemon of the adultery and encourages Philemon to forgive and forget. Philemon does not mean to kill Matilda, on whom he dotes. But humiliation has a terrible power, and every gracious gesture on stage is the unspoken (though not unsung) reminder that this township is victim of the terrible humiliation of apartheid.

What makes The Suit exceptional theater is the sheer graciousness of those gestures. Every actor moves like a dancer. Every actor speakers like singer. And song pervades all. Pianist and accordionist Mark Christine, trumpet player Mark Kavuma and guitarist Arthur Astier underscore the production with arrangements of Schubert songs, South African songs, African American blues, The Blue Danube and, of course, Bach.

The music mainly serenades. Schubert’s Death and the Maiden may not be a subtle indicator but, heard played by a wandering accordionist, it is easy to ignore its significance. And that is the brilliance of The Suit. Brook has long been streamlining theater and opera, breaking down the distinctions between the narrative and the lyric stage. Movement is, for Brook, a purifying process. Music and speech only have meaning if movement does.

Three years ago, also with the help of Estienne and Krawczyk, Brook reduced Mozart’s The Magic Flute down to its ritualistic essences, removing the magic and retaining the humanity. In The Suit, however, the horrors won’t go away. But by making theater, music and dance inseparably one, Brook’s art reaches that cleansing Bachian peak where beauty and humanity endure.

Mark Swed – The Los Angeles Times