Tags

aria, Bach Collegium Japan, Bible, BIS, cantata, chorale, chorus, Cross of the Order of Merit, Deutsche Grammophon, Early Music Vancouver, fanfare, German, German Record Critics’ Award, Handel, harpsichord, hymn, John Eliot Gardiner, John Ibbitson, Leipzig, Masaaki Suzuki, Mass in B minor, motet, oboe, Penguin Guide to Recorded Classical Music, recitative, rehearsal, Robert von Bahr, soprano, St. Matthew Passion, Stockholm, The Globe and Mail, Tokyo, Ton Koopman, Vivaldi

In 1993, when Robert von Bahr received a letter at his Stockholm office proposing that his company, BIS Records, undertake a complete cycle of all two hundred Bach cantatas with someone named Masaaki Suzuki conducting a Japanese choir and ensemble, he reacted, he recalls, with “uncontrollable laughter.” But the proposal also came with an offer of a plane ticket, so von Bahr flew to Tokyo to hear Suzuki conduct his Bach Collegium Japan. “And then,” he remembers, “the sun came up.”

In 1993, when Robert von Bahr received a letter at his Stockholm office proposing that his company, BIS Records, undertake a complete cycle of all two hundred Bach cantatas with someone named Masaaki Suzuki conducting a Japanese choir and ensemble, he reacted, he recalls, with “uncontrollable laughter.” But the proposal also came with an offer of a plane ticket, so von Bahr flew to Tokyo to hear Suzuki conduct his Bach Collegium Japan. “And then,” he remembers, “the sun came up.”

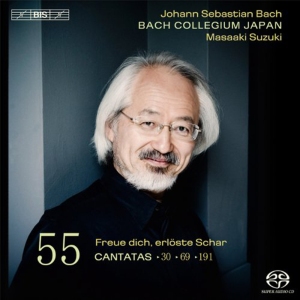

Now, twenty years later, BIS is releasing the fifty-fifth and final volume of Bach Collegium Japan’s traversal of the Bach cantatas. While there have been other cantata cycles, none has taken this long, been prepared with such care or been greeted with higher praise.

“Although the excellence of rival surveys is not in doubt, this Japanese survey is the strongest and most consistent,” the venerable Penguin Guide to Recorded Classical Music declared, stamping it “an obvious first choice.”

“It’s beautifully crafted,” said Matthew White, the Canadian countertenor and artistic director of Early Music Vancouver. He sang in Vol. 23 of the series. Suzuki’s cycle “balances rigor and passion, which Bach’s music embodies in a very simple way,” he said. “And when I was rehearsing with them, I felt them embrace that.”

How did thirty-odd mostly Japanese singers and musicians a world away from Germany deliver what many believe is the greatest-ever interpretation of this cornerstone of the Western canon? They practiced. For two decades.

Suzuki became obsessed by the cantatas as a music student in Tokyo. He learned that as a church composer in Leipzig, Johann Sebastian Bach was expected to deliver a new cantata for every Sunday service. Each cantata is about twenty minutes long and consists of two choral movements and several arias and recitatives for solo voice, with the texts adapted from hymns or Bible passages and the singers accompanied by a small ensemble.

For Bach, it was journeyman work, but it was also the very core of his life as a composer. The cantatas are chock full of beauty – an exultant chorus, a soprano’s voice floating above an accompanying oboe, weaving melodic lines, a stolid Lutheran hymn transfused with passion.

“The texts were so different and the polyphonic structure of Bach’s music is so fascinating to me, I couldn’t stop listening to the different recordings,” Suzuki said in a telephone interview. “And . . . afterward I couldn’t resist performing these works myself.”

From 1979 to 1983, he studied period performance in the Netherlands – playing early classical music with the instruments, ensemble sizes and performance practices that would have been used at the time the music was composed. He then returned to Japan to teach, establishing the Bach Collegium Japan in 1990. In 1995, Suzuki and von Bahr began to record cantatas.

It was a rocky beginning. “We had many discussions and arguments about the way of recording, and also about performance style with period instruments and so on and so on, because he was the producer as well as the president [of BIS],” Suzuki remembers. “And our members thought: ‘It’s not possible to work with him.’” But Suzuki’s performances left von Bahr ecstatic, and the entrepreneur eventually convinced Suzuki that he was in it for the long haul. Very long, as it turned out.

Unlike other traversals, which were often recorded in haste while everyone was available, or with one conductor beginning the cycle and another completing it, Suzuki and von Bahr resolved to rehearse intensively – “at the very beginning it took us two hours just to perform ten bars,” Suzuki remembers – and then perform the cantatas in concert before recording them.

Over the years, individual musicians changed, but the Suzuki sound remained remarkably consistent – technically perfect, vocally pure, yet imbued with a spirituality imbedded in Suzuki’s deep Christian faith.

Initial releases were treated with polite caution – at best. One Italian critic opined that the Japanese throat was physiologically incapable of reproducing German speech. When a Spanish reviewer criticized the German pronunciation of the chorus, von Bahr phoned him and began complaining in German, only to discover the critic didn’t know a word of the language. “He was fired,” von Bahr recalls with some satisfaction.

Suzuki believes that being Japanese has its advantages when performing Bach. “If our choir has a Japanese character, and not a European one, then it makes the voices and the intonation very pure. And in Japanese culture as well, it is not so important to project your personality, but to be homogeneous with others, and that can work very well in a choir,” he said.

It didn’t take the critics very long to come around – and stay around. “Standards haven’t slipped an inch,” Fanfare, an American classical music magazine, raved in 2009, judging the cycle “a set for the ages.”

One French critic wrote about the music’s “clarity of purpose, sweep . . . the sumptuous timbre of instruments, innate sense of ideal orchestration . . . and wonderfully luminous chorus, which hit all the marks.”

“Their music-making is contained and precise,” White observes, “but punctuated by moments of emotional outburst that transcend all that beautiful accuracy.”

The Germans not only warmed to this Asian interpretation of their sacred Bach cantatas, they awarded Suzuki and his ensemble the Cross of the Order of Merit of the Federal Republic of Germany in 2001, the German Record Critics’ Award in 2010 and, in 2012, the Bach Medal, presented by the City of Leipzig.

No one is more surprised than Suzuki that they pulled it off. “I never thought until recently that we could complete it,” he said. “Whenever I was asked how long it would take, I would say: ‘Another fifteen years.’ And then: ‘Another fifteen years.’” After all, times were hardly good for the classical music recording industry. A cycle by the Dutch conductor Ton Koopman, Suzuki’s teacher, was interrupted when his recording company went bust. (Another company took up the torch, allowing the cycle to be completed.) Deutsche Grammophon abandoned a planned cycle by the British conductor John Eliot Gardiner. (He completed it with his own money.)

But not only did little BIS survive, the Suzuki cantatas “have been our bread and butter,” says von Bahr. A typical release sells ten thousand copies; some have sold much more. (That’s a strong number, considering other BIS releases usually sell around three thousand copies.)

It hasn’t ended with the cantatas. Along the way, the Bach Collegium Japan has recorded acclaimed performances of the Mass in B minor (BWV 232), the St. Matthew Passion (244b) and the motets, as well as works by Handel, Vivaldi and other composers. And, to keep himself busy, Suzuki is also recording a complete set of Bach’s music for harpsichord.

For von Bahr, the success of the Suzuki cycle speaks not to one culture interpreting another, but to music that transcends cultures entirely, proving that “it is a language that anyone can understand, if they’re willing to listen.”

John Ibbitson – The Globe and Mail