Tags

alto, Arnstadt, bass, Boulder Bach Festival, Brandenburg Concertos, Buxtehude, cantata, Cöthen, chorale, Es wartet alles auf dich, Franz Tunder, Herz und Mund and Tat und Leben, hymn, Jesu Joy of Man’s Desiring, Johann Crüger, Johann Kuhnau, Lübeck, Leipzig, Martin Luther, Mass in B minor, Mühlhausen, Mer hahn en neue Oberkeet, organ, performance practice, Reformation, Rick Erickson, Saxony, scenery, sinfonia, soprano, tenor, The Holy Trinity Bach Players, Thuringia, Zimmermann’s Coffee House

Edward McCue (EM) Please tell us more about the cantatas as they have been performed less frequently here in Boulder than some of Bach’s other works.

Rick Erickson (RE) I really wanted to begin this season of my first year with cantatas, rather than what are sometimes called “Bach’s major works.” Cantatas are the heart of Bach and employ both brilliant instrumentation and writing for voices in both ensemble and in solo roles.

On the Third of March we’ll be featuring two cantatas that are, to be honest, particular favorites of mine. Herz und Mund and Tat und Leben (BWV 147) contains the famous “Jesu, Joy of Man’s Desiring.” It’s a rip-roaring cantata, in two parts, that employs oboes, trumpet, strings and choir in a brilliant opening movement. For the voices I thought that I should select literature that had some real meat on it, so I knew that this would be a great place to start, along with Es wartet alles auf dich (BWV 187).

EM Many of us Bach fans know that both chorales and cantatas deal with sacred themes, but we’d like to know more, such as, what was the origin of the chorale tradition, and what were cantatas intended to do?

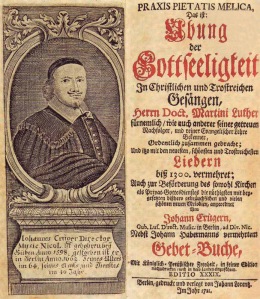

RE Bach, of course, lived almost his entire life in Thuringia and Saxony, now states in Germany, where the Lutheran influence was powerful. Martin Luther himself, at the time of the Reformation, had encouraged and had, in effect, created a great body of chorales that were intended to literally speak the Gospel with the voice of the people. This hymn form, the chorale, was also often a didactic teaching statement. Luther said, “Sing safe into your heart and that way also remember it,” so the chorale became a central means of Lutheran expression.

The chorale led to the production of a huge amount of literature, first of all for organ, as the organ was, and still is, employed in the Lutheran services. Chorale preludes have occupied many pages of the organ literature from very early on, through Bach and indeed until today.

The chorale led to the production of a huge amount of literature, first of all for organ, as the organ was, and still is, employed in the Lutheran services. Chorale preludes have occupied many pages of the organ literature from very early on, through Bach and indeed until today.

By the time Bach came along, the chorale had morphed and had a very real presence in the cantatas. Franz Tunder and Johann Crüger were some of the first people to write cantatas incorporating chorales and developed this expression into a high art form. Bach grew up knowing the cantata form very well as his uncles wrote them, as did many other composers around him.

Bach may have been most influenced by visiting Buxtehude in Lübeck around the age of eighteen. He walked all the way, spent a few months, probably absorbing all he could, and came back to Arnstadt.

Bach’s cantata output even probably proceeds Arnstadt, but certainly around the time of 1707 or so, Bach had begun putting his pen to the cantata form. A brilliant example of this writing was during his brief period in Mühlhausen. He then wrote only sporadically through his time in Cöthen as the court itself was Reformed, but Bach did write a few cantatas for the Lutheran church there. But when he came to Leipzig, he entered a world in which the Kantor, which was Bach’s office title, was expected to produce a cantata every week, except during the seasons of Advent and Lent. In that capacity Bach succeeded Johann Kuhnau, who had already written a large number of cantatas, but Bach decided to compose his own series of cantatas for Leipzig rather than reuse his predecessor’s works.

About a third of these cantatas that Bach wrote for Leipzig are lost, unfortunately, but the ones that survive are great examples of the high art form which was employed as a normative event in the life of the church.

Just imagine what is must have been like for Bach to piece together a new cantata on a weekly basis. During twenty-five weeks of the year at Holy Trinity in New York, we prepare and perform cantatas in liturgy, and simply to do them is an enormous amount of work. I can’t imagine putting on top of that the writing of them.

Just imagine what is must have been like for Bach to piece together a new cantata on a weekly basis. During twenty-five weeks of the year at Holy Trinity in New York, we prepare and perform cantatas in liturgy, and simply to do them is an enormous amount of work. I can’t imagine putting on top of that the writing of them.

And think about the workforce that Bach had to manage in order to perform the works. He had to prepare four choirs from the school, rehearse the town instrumentalists, stay on top of the copyists who were preparing the performance materials, and keep the whole enterprise organized according to the expectations of the municipality as well as the church. But the cantatas are, in my mind, at the heart of Bach’s writing just because they were The Job.

EM I still don’t have a clear sense of whether the chorale was a hymn for congregational singing or whether professional choirs always sang the chorales.

RE The chorale was, first of all, the principal hymn of the assembly, of the people; however, the way in which the chorale was almost always done, even from the very beginning, was in alternation so that the professionals would sing a stanza, then all the people would sing a stanza, and so forth, back and forth. This was because some hymns that had fourteen, twenty, even twenty-one stanzas, and it could get to be pretty exhausting if everyone sang all the way through. Alternation was the way in which it was often done, and I think that singing in alternation is what finally led to the cantata itself: a song shared between professionals and all the people.

EM I suppose, then, that the Leipzig congregations were eager to attend the cantata performances because there was something new in store for them every week.

RE I think it’s very fair to say that because the opera in Leipzig had closed down two years before Bach arrived, so, quite frankly, these Sunday cantatas, which were performed on other feast days as well, were very popular events and were probably the central entertainment in the community. They had a liturgical role, a meditative, spiritual role, absolutely, but, quite frankly, I’m certain that they were intended for the delight of the people as well.

EM How do these sacred cantatas compare to other Bach works that are known as secular cantatas?

RE Bach was kicking up his heels when his Collegium Musicum of University musicians and he performed some of the really ribald secular cantatas at Zimmermann’s Coffee House. The “Peasant Cantata,” Mer hahn en neue Oberkeet (BWV 212), is a great example as it was written as an homage cantata in a colloquial Saxon dialect of German, a particular delight and surprise. Other secular cantatas are also fairly bawdy in nature and play upon the foibles of the general population of the time.

The writing in the secular cantatas is distinctively different and almost, in some places, points to the rococo. For example, in the Peasant Cantata, there are places which sound peasant-like, with droning bagpipes, which would be a very unusual gesture in a sacred cantata. And then there are a few cantatas that dance between the two forms. The wedding cantatas are almost divided in half between secular and sacred, which I find to be most intriguing.

The writing in the secular cantatas is distinctively different and almost, in some places, points to the rococo. For example, in the Peasant Cantata, there are places which sound peasant-like, with droning bagpipes, which would be a very unusual gesture in a sacred cantata. And then there are a few cantatas that dance between the two forms. The wedding cantatas are almost divided in half between secular and sacred, which I find to be most intriguing.

The body of secular cantatas is much smaller than the body of sacred cantatas, amounting to no more than roughly ten to a dozen, and in Bach’s day they played a different role because they weren’t performed in a church. Today, I think that we might want to consider staging productions of the secular cantatas in a theater.

EM How would you recommend that our patrons prepare themselves for the upcoming Festival performances of sacred cantatas?

RE You know, the cantatas are such vivid expositions of all of Bach’s styles and musical languages. There is tremendous variety among choral movements, including many based on chorales. There are also instrumental sinfonia moments and really astonishing writing for soprano, alto, tenor and bass with obbligato instruments. I simply think that this wealth of expression, coupled with the thought that Bach developed one of these many-faceted jewels each week, will astound our listeners.

What I want to underscore is that, while the Brandenburg Concertos (BWV 1046-1051) and the Mass in B minor (BWV 232) were carefully prepared, elegantly written out compositions dedicated to distant patrons, the cantatas, as polished and complete as they were, were dedicated to the hearts and minds of the people of Leipzig. It is these very human expressions, contained within the cantatas, that impress me most about Bach. If we take the time to understand the cantatas, we end up knowing Bach in a much more intimate way.

EM One cantata movement that you mentioned earlier was the “Jesu, Joy of Man’s Desiring.” I mean, it’s an international hit, even for us in the twenty-first century. Would you go so far as to say that Bach was attempting to write a series of hit pieces for every Sunday and that, when they were strung together, they were not only emotionally satisfying but, intellectually, they helped to amplify the Gospel theme of the day?

EM One cantata movement that you mentioned earlier was the “Jesu, Joy of Man’s Desiring.” I mean, it’s an international hit, even for us in the twenty-first century. Would you go so far as to say that Bach was attempting to write a series of hit pieces for every Sunday and that, when they were strung together, they were not only emotionally satisfying but, intellectually, they helped to amplify the Gospel theme of the day?

RE Look, like in Boulder, the Leipzig people were, for the most part, a very well-educated population. They absolutely would have known the chorales, understood the allusions in the chorales, and have taken home something new because of the intellectual experience.

Every cantata is an event for both the enjoyment of the ear and for the intellect. In a sense it’s happy work, but it’s hard work, to hear Bach and to follow Bach. But that makes it very rewarding work, and that’s how, by presenting his cantatas, the Boulder Bach Festival plays an important role in our community.

Very interesting comments, Rick.