Tags

acoustics, archlute, bell, brass string, chitarrone, color, dynamics, foreshortening, Gergely Sárközy, gut string, Hamburg, harpsichord, Hungaroton, jack, Jakob Adlung, Jena, Johann Christoph Fleischer, Johann Friedrich Agricola, Johann Nikolaus Bach, lautenwerk, lute, lute stop, lute-harpsichord, manual, metal string, organ, Partita in C minor, plectrum, quill, resonator, soundboard, spinet, stop, tension, Theorbenflügel, theorbo, timbre, Zacharias Hildebrandt

Over a period of three centuries there are numerous references to gut-stringed instruments that resemble the harpsichord and imitate the delicate, soft timbre of the lute, including its lower-sounding variants, the theorbo and chitarrone (or archlute) or the harp, but little concrete information is available. Not a single instrument has survived, nor is any contemporary depiction known apart from a rough engraving of the early sixteenth century. Fewer than ten lute-harpsichord (“lautenwerk”) makers are known, and there are reasonably detailed descriptions of instruments made by only two or three of them. Nonetheless, the instrument is mentioned fairly frequently in music books of the early seventeenth to the mid-eighteenth century.

Over a period of three centuries there are numerous references to gut-stringed instruments that resemble the harpsichord and imitate the delicate, soft timbre of the lute, including its lower-sounding variants, the theorbo and chitarrone (or archlute) or the harp, but little concrete information is available. Not a single instrument has survived, nor is any contemporary depiction known apart from a rough engraving of the early sixteenth century. Fewer than ten lute-harpsichord (“lautenwerk”) makers are known, and there are reasonably detailed descriptions of instruments made by only two or three of them. Nonetheless, the instrument is mentioned fairly frequently in music books of the early seventeenth to the mid-eighteenth century.

Much of the available information relates to three eighteenth-century German instrument makers: Johann Christoph Fleischer of Hamburg, Johann Nikolaus Bach and the organ builder Zacharias Hildebrandt.

Fleischer built two types of instrument. The smaller had two 8-foot gut-stringed stops with a compass of about three octaves; in the lower two octaves these could be coupled with a 4-foot stop analogous with the pairs of octave-tuned bass strings (courses) on the lute. Below the soundboard of the instrument, an oval resonator in the shape of a shell, resembling the body of a lute, was attached.

Fleischer called his larger instrument the “Theorbenflügel” (theorbo-harpsichord). Its two gut-stringed stops together made up a double-tuned, 16-foot stop, with the pairs in the lower octave-and-a-half tuned an octave apart and in the upper range in unison. In addition, there was a 4-foot metal-stringed stop, and the combination of the 4-foot and the 16-foot stops produced a “delicate and bell-like” tone. This larger instrument was in the shape of a regular concert harpsichord.

Johann Nicolaus Bach, a second cousin of Johann Sebastian, was a composer, organist and instrument maker in Jena. He, too, built several types of lautenwerk. The basic type closely resembled a small wing-shaped, one-manual harpsichord of the usual kind. It only had a single gut-stringed stop, but this sounded a pair of strings tuned an octave apart in the lower third of the compass and in unison in the middle third to approximate, as far as possible, the impression given by a lute. The instrument had no metal strings at all.

According to contemporary accounts, even this simplest of versions made a sound that could deceive a professional lutenist, a fact considered almost miraculous at the time. But a basic shortcoming was the absence of dynamic expression. In order to remedy matters, J. N. Bach also made instruments with two and three manuals whose keys sounded the same strings but with different quills and at different points of the string, thereby providing two or three grades of dynamic and timbre. J. N. Bach also built theorbo-harpsichords with a compass extending down an extra octave.

J. S. Bach’s connection with and interest in the lautenwerk was considerable. He clearly liked the combination of softness with strength which these instruments are capable of producing, and he is known to have drawn up his own specifications for such an instrument to be built for him by Hildebrandt. In an annotation to Adlung‘s Musica mechanica organoedi, Johann Friedrich Agricola described a lautenwerk that belonged to Bach:

The editor of these notes remembers having seen and heard a “Lautenclavicymbel” in Leipzig in about 1740, designed by Mr. Johann Sebastian Bach and made by Mr. Zacharias Hildebrand, which was smaller in size than a normal harpsichord but, in all other respects, similar. It had two choirs of gut strings and a so-called little octave of brass strings. It is true that in its normal setting (that is, when only one stop was drawn) it sounded more like a theorbo than a lute. But if one drew the lute stop, such as is found on a harpsichord, together with the cornet stop [the undamped, 4-foot brass stop], one could almost deceive professional lutenists.

The inventory of Bach’s possessions at the time of his death reveals that he owned two such instruments as well as three harpsichords, one lute and a spinet.

The lautenwerk therefore differs from the harpsichord in several important respects. While historical references indicate differing approaches to design, there is general agreement that whereas harpsichords are designed to be strung in metal, the use of gut strings is of primary importance in a lautenwerk. However, simple replacement of metal strings with gut will not give satisfactory results.

Generally, a gut string requires a longer scale (or length at a given pitch) than a metal string, which in turn infers a larger instrument. Pitch for a given string length however, is a function not only of length but also of string material and tension. The lower-pitched strings of the lute-harpsichord are thicker and under less tension – a technique known as “foreshortening.” Thus lautenwerks are often smaller than their metal-strung relatives. Extreme foreshortening of the scale, in comparison to the harpsichord, reduces the tension that a lautenwerk must bear. Lighter construction is made possible, thereby enabling a lautenwerk to better respond to the less energetic gut string. This is especially true of the soundboard, which can be half the thickness normally found in harpsichords.

Gut stringing has other implications for lautenwerk design. As gut strings have more internal friction than their metal counterparts, they generally have less sustain, allowing one to dispense with dampers to a large degree. Individual instruments will dictate where dampers are needed and how effective they need be, but one rarely finds a lautenwerk fitted with dampers on every string. Any resulting “over-ring” is likely to enhance the lute-like effect.

The lautenwerk also demands special attention concerning string layout. Thick gut strings vibrate more vigorously than thin metal ones at higher tension. This requires that more space be given between adjacent strings to avoid interference. This consideration encourages the builder to keep his design simple. Two choirs of gut strings seems to be the practical maximum, although a third choir strung in brass is sometimes found.

Harpsichords normally have one dedicated jack per string. Lautenwerks often have more than one jack independently serving the same string. Tonal variation is achieved by plucking the string at different points along its length. Dynamic and color variation can also be pursued by using plectra having different properties. This sort of elaboration is most often reserved for instruments having more than one manual. Adding more strings to achieve tonal interest is avoided, and resonant construction is maintained.

As noted above, the internal volumes of some of Fleischer’s lautenwerks were determined by a dome-like structure shaped much like the back of a lute, and indeed modern instruments have been made in which a “lute shell” defines the exterior shape of the instrument. Internal structures placed below the soundboard are also sometimes found. Other modern makers adopt construction methods normally associated with other keyboard instruments.

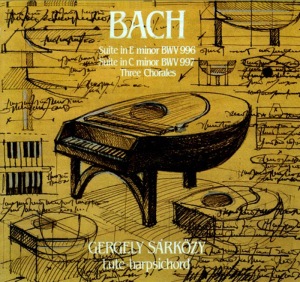

Of the few attempts to reconstruct and record a lautenwerk, one of the more successful is the instrument built for the player Gergely Sárközy who performs a work that has traditionally been assigned to the lute, Bach’s Partita in C minor (BWV 997), on a recording by Hungaroton.

– Baroque Music